Decoy pricing and price anchoring are two different techniques that can increase your average proposal value in multi-option pricing.

(If you’re not using multi-option pricing then you’re missing the lowest hanging fruit on the profit tree. Get yourself a copy of Pricing Creativity and fix that first.)

Both techniques are effective in the right circumstances, and they’re similar enough that they often get confused for each other.

Each of them add an extra option to the consideration set, typically a third but sometimes a fourth. From there, they differ quite a bit.

Decoy Pricing

Decoy pricing adds an extra “decoy” option in the middle between two legitimate offers as a way of nudging purchasers toward the higher priced of the two options.

Dan Ariely popularized decoy pricing in his book Predictably Irrational when he wrote about an experiment he ran on the pricing page of The Economist magazine’s website. He presented three subscription options:

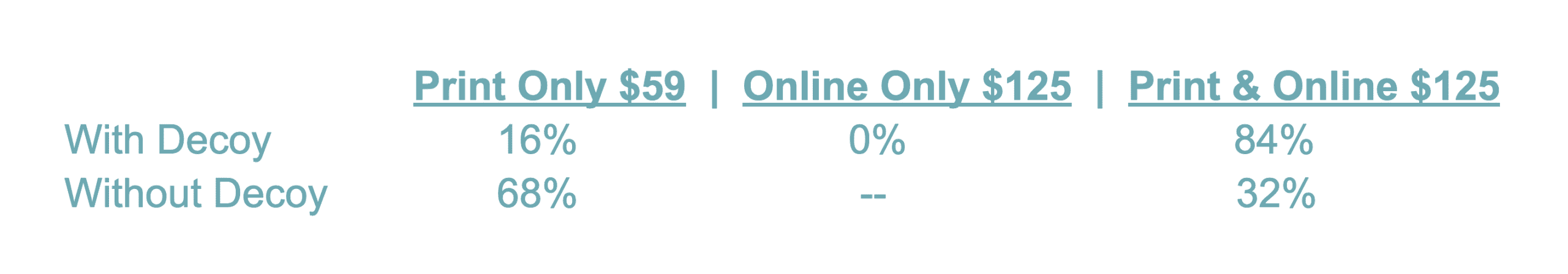

Print Only $59 | Online Only $125 | Print & Online $125

It’s pretty clear from the options and prices that the decoy in the middle was never meant to be bought. And it wasn’t. (It was selected precisely 0% of the time in Ariely’s test. See below.)

Not all decoys are this obvious. There is usually a small but nominal price difference between the decoy and the third, most expensive option, but it’s still easily spotted.

Movie-theatre popcorn is a classic real-world example. You’ll often see prices like this:

Small $4 | Medium $7 | Large $7.95

Nobody buys the medium. Its real function is to make the large look irresistibly good.

If you’re hungry, your actual choice is between the medium and the large, and for only 95 cents more, the large is a “no-brainer.” But even when your choice is supposed to be between the small and the medium, the presence of the overpriced decoy in the middle shifts you upward, making the large feel like the rational, value-maximizing choice.

This is the decoy effect, where the middle “decoy” option is overpriced relative to the value the purchaser gets from the only slightly more expensive third option. The academic term for this is the asymmetric-dominance effect. The medium is dominated by the large on every meaningful attribute, but not dominated by the small. This creates a one-sided comparison that pushes you toward the large.

Note Ariely’s results from selling The Economist subscriptions below, and how they changed when the decoy was removed.

Clearly, decoys work to push people to higher priced options. Results like these have been replicated in other studies. The numbers vary but the direction holds.

Price Anchoring

I’ve written extensively about price anchoring in blog posts and books, I’ve done podcasts on it and this past September price anchoring was the topic of The Conversation, so I’ll do only a brief overview here.

The anchoring effect is the idea that the first piece of information on a subject skews the final decision on that subject. When it comes to price anchoring, salespeople anchor high in negotiations and buyers anchor low. As a seller of expertise, you anchor in The Value Conversation and you reinforce that anchor in your proposal where you lead with the most expensive option. (This is explained more fully in The Four Conversations.)

Like a decoy, anchoring seeks to nudge people to the more expensive options, but unlike a decoy, the additional anchor option is inserted as the most expensive option, not in the middle. The expectation is that the new, high anchor will move people away from the lowest option to the middle, with some but fewer people selecting the anchor and some still selecting the cheapest in a classic bell-shaped distribution curve.

Comparing and Deciding Between Decoys and Anchors

Decoys can move the client from your cheapest option to your most expensive by putting a carefully architected false choice in the middle.

High anchors can move the client’s safe zone from their budget (your cheapest option) to the middle option by leveraging a principle known as extremeness aversion, which says that when faced with options, people retreat from the dangers of the edges to the safety of the middle. (The danger in the anchor is overpaying, but the anchor reveals a danger in the client’s budget: underbuying. The safe middle option becomes a hedge against both.)

The Sale Is the Sample of the Engagement to Follow

While the decoy of a clearly inferior middle option inflates the perceived value of the more expensive option, what does it do to the client’s emotional state?

When you choose to maximize value and pay $7.95 for a large popcorn when you really wanted less, a part of you feels like you were manipulated into it through the use of something that is by definition “fake” or “meant to distract attention.”

That seems to be acceptable collateral damage in a transactional popcorn purchase under $10, but what are the implications in a sale of expertise where the sale is the sample of the engagement to follow, where, through your selling and pricing, you demonstrate who you are and what it will be like to work with you?

Selecting Between the Two

I think decoys are perfectly appropriate for selling low-price, high-volume productized services, where a little collateral damage can be tolerated.

For expensive, mission-critical expertise, I prefer the anchoring technique because it’s more aligned with the best interests of the client, and there’s nothing fake about it.

Decoys are slightly manipulative in a way that anchors are not. Yes, anchors push the client to spend more but they do that first and foremost by challenging the client to think bigger. At its best, anchoring is as much about emboldening the client to view the project strategically, as an opportunity to invest in transformation instead of a project whose costs must be minimized. What higher purpose can an outside expert serve?

With all multi-option proposals, the client gets the final say. And while you get to architect the choice with decoys and anchors, the former is a pricing gimmick and the latter is you embracing the challenge to inspire the client to think bigger and bolder.

What do you want from the experts you hire?

Do what you would have them do.

-Blair