There is a fundamental but poorly understood principle of business that has deep implications for all creative firms, their clients and the often tense relationships between them.

The center of this tension, as you will see, is in the client’s marketing procurement department (new podcast on this niche topic introduced at the bottom) but it extends everywhere across both organizations.

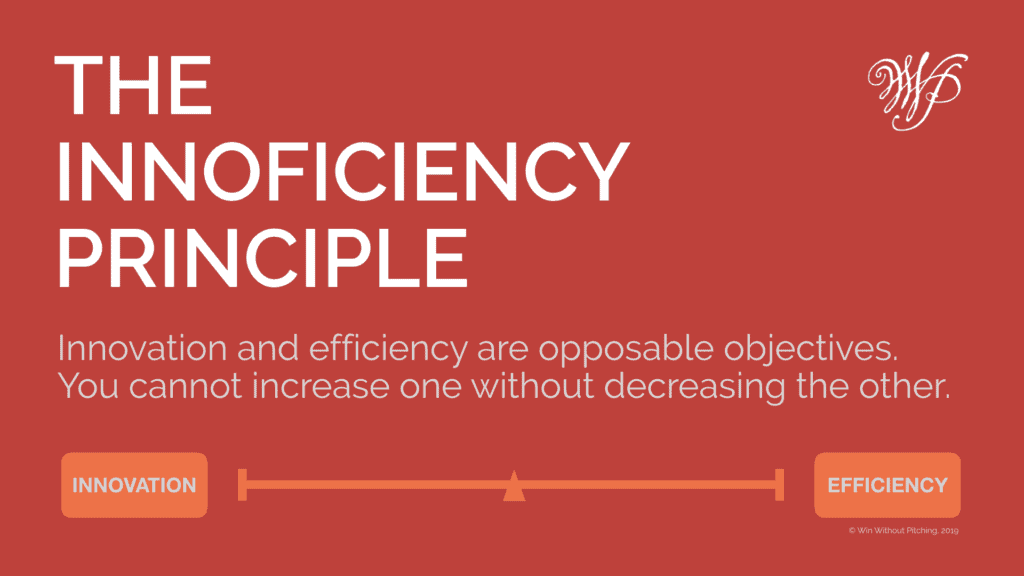

It is a problem of innovation, efficiency and their relationship to each other. I’ve coined a word to describe the principle and the problem: innoficiency.

Here, I lay out the Innoficiency Principle and the Innoficiency Problem, showing the downstream implications in your clients’ businesses and in your own firm, illuminating many of your professional frustrations.

The Innoficiency Principle

The Innoficiency Principle states that innovation and efficiency are mutually opposable goals. In any reasonably functioning organization, one cannot be increased without decreasing the other.

Every organization exists somewhere on a spectrum between maximum innovation at one end and maximum efficiency at the other. The same can be said of any department within an organization and of any individual within a department.

The tension between these poles affects almost every decision the organization makes. When we seek gains in one direction we cannot help but move further from the other.

The Innoficiency Problem

The Innoficiency Problem is to be ignorant of the principle and to think an organization, department or individual can increase either innovation or efficiency without decreasing the other. It cannot. “Efficient innovation” is an oxymoron.

Defining Innovation and Efficiency

To understand why these two goals are mutually opposable we need to define them.

Innovation is not so easily defined. The best definition I’ve encountered comes from Nick Skillicorn, an innovation consultant who surveyed 15 other innovation experts for their definition and constructed his from their most common elements:

“Innovation is executing an idea [that] addresses a specific challenge and [creates] value for both the company and the customer.”

The components of innovation in Skillicorn’s definition are:

- Newness in either the idea or the execution

- Execution (not just the idea)

- Problem solving

- Value creation that accrues to both the organization and the customer

Efficiency is easier to define. The technical definition of efficiency is “the ratio of useful work relative to the input of energy.” Or: output relative to input.

When we say someone or something is “efficient” we are implying “high efficiency,” which means inputs are translated directly into outputs with little waste. In a machine, input energy tends to be wasted in the form of friction or heat. In a person, waste is often measured in time. In an organization, it’s most commonly time and money.

To pursue efficiencies is to seek to achieve more with less, to reduce waste, which is captured in the following definition:

“Efficiency is the goal of increasing the output in a system (organization, department or person) relative to the input.”

Innovation may result in efficiencies (a form of value, the creation of which is the goal of innovation), but the act of innovating is inherently wasteful and therefore itself inefficient. This is the Innoficiency Problem in a nutshell.

A culture that values efficiency over innovation will not allow its constituent components (departments or individuals) to waste the necessary resources of time and money to properly innovate.

“…the act of innovating is inherently wasteful and therefore itself inefficient”

The degree to which any organization values innovation or efficiency over the other is baked into the culture. Every member of the organization intuitively understands the tolerance for waste, that is, how much the organization is willing to sacrifice in order to try to create new value.

While the organization itself rests at a state of innoficiency equilibrium, there are always departments and individuals pulling in one direction or the other, either trying to move the organization to what they see as the correct culture of innoficiency or, more often, optimizing to the goals of their department rather than those of the organization.

The classic example is a marketing department that pursues innovation and a procurement department that pursues efficiency.

The Inevitable Tilt Toward Efficiency

Businesses are born in a burst of innovation and, as they succeed and grow, begin the march along the innoficiency spectrum away from their innovative beginnings toward greater efficiencies.

This tilt toward efficiency in a successful company is inevitable––a law of the universe like entropy, the second law of thermodynamics.

Entropy says the universe (and any other closed system, like a sandcastle) moves from order to disorder or randomness over time. The sandcastle crumbles instead of arranging itself into a bigger or more precise structure. The universe marches to its inevitable “heat death” from the random dispersal of all matter and energy.

A business is an open system, however, and can bring in new energy—in the form of management layers (people), systems, software and other agents of optimization—to wage the battle against entropy to maintain order.

The inevitable battle in a growing company is always pushing away from the gravity of chaos and waste toward greater efficiency. There is no durable success at scale without additional energy allocated to the pursuit of greater efficiencies.

A culture of innovation, however, must tolerate some waste. Thus the tension. Entropy is waste. (One technical definition of entropy is the measure of unusable energy in a system.)

A culture that will not tolerate waste cannot innovate and is left vulnerable to younger, more chaotic and innovative competition.

“Nice Theory, But…”

Most people, when hearing of the Innoficiency Principle for the first time, reject it. They can think of times when they, or organizations they are attached to, have been both innovative and efficient.

While this is common in isolated incidents (like rare dysfunctional cultures where some order is needed to accomplish anything, and the occasional innovations that can result from constraint-driven exercises) it is not sustainable. Again, this is an issue of culture. The more efficiency-seeking a culture is, the less it tolerates waste and the more precarious the positions of the risk-taking innovators in the organization.

An occasional constraint-driven exercise can be a powerful tool of innovation but a culture of constraint will suffocate innovation and push the innovators out.

The waste that must be tolerated to create a culture of innovation comes in many forms, including free time (people with their feet up on the desk), long-shot R&D investments, hiring brilliant and expensive people before there’s a role for them and freedom to fail. Sounds like a start-up, doesn’t it?

Innoficiency in Societal Cultures

The tension inherent in the Innoficiency Principle is evident in the culture of a business, but we also associate cultures with countries and ethnic groups.

America is the most economically successful country on the planet because it is relatively young, born of a revolution, and its ideals are still out on the innovation end of the innoficiency spectrum. Only recently out of start-up mode, America prizes innovation and tolerates waste.

Take one of the forms of waste already mentioned: freedom to fail.

American culture allows for failure in a way others do not, as long as one is seen to be trying. Bankruptcy brings some stigma in America, but it is not insurmountable. The stories of people making good after failed attempts are illustrative examples of living the American dream.

Walt Disney, P.T. Barnum, Milton Hershey, Henry J. Heinz, Henry Ford and William Durante all went bankrupt before going on to great successes. They are remembered for those successes and lauded for overcoming adversity. The mild stigma of early failure is more than wiped out by effort, risk and later success.

Donald Trump put his business into bankruptcy after inheriting $413 million and twenty five years later he was elected president. Abraham Lincoln bankrupted more than one business, declared personal bankruptcy, lost eight elections and suffered a nervous breakdown but he is remembered for none of that. Instead, he is today the highest rated president in US history.

In America, you are allowed to fail, as long as you try. When you do ultimately succeed, all failures are forgiven.

We can see this freedom to fail in the hit-maker model of Hollywood studios, New York publishers and Silicon Valley venture capital firms—all built on the idea that 10 or 20 ventures will fail but one win makes it all okay.

America prizes innovation and understands that it is messy and wasteful by nature. It intuits that one cannot consistently innovate efficiently, that risks and waste are the prices that must be paid for a culture of innovation.

Contrast American culture to other, older cultures where failure brings shame to the family—irredeemable, multi-generational, dishonor so disabling that few risks are taken—and you will understand why products are born in innovation-seeking America and produced in efficiency-seeking cultures elsewhere.

The Life Cycle of Your Clients’ Businesses

In the beginning, a business is spawned by a supernova of an idea, followed by a whole lot of frenetic effort.

It is the very definition of innovation: something new, in idea and execution, that solves a problem and creates value for the customer and the organization. It is chaotic and vibrant, hugely inefficient and likely to fail. This describes almost every start up.

There is no concern about profit taking in the beginning, all operating profits—if any—are reinvested in the growth of the organization and it is understood that there will be much experimenting and many failures. “Fail forward” is the motto.

But as the company grows and encounters problems associated with scale, it needs systems, processes, order. Layers of middle management are added, ERP software is purchased, supply chain management consultants are brought in, strategic sourcing initiatives are launched and procurement departments are born. Chaos is harnessed and success is realized.

At some point Wall Street demands the company they lauded as a darling must quit reinvesting all the operating profits into building a better future and begin to distribute some of those profits now. Costs are managed even more closely. More and more power accrues to finance, procurement and other efficiency-seeking departments.

The innovators, who need a certain freedom and tolerance of “big bets,” risk and failure in the same way they need oxygen, start to feel suffocated and they begin to leave.

While once seen as a growth stock trading at a high price-to-earnings ratio, the multiple declines as the market realizes the company’s future, relative to its current position, isn’t as big as it used to be.

The shareholder base has changed to a more conservative investor who keeps pushing for the profits to be distributed instead of reinvested. They want stability and predictability in their dividends.

The pressure to reduce waste is pervasive: zero-based budgeting, online reverse auctions, in-housing, off-shoring and outsourcing are the words heard in the hallways. If innovation happens at all, it’s through acquisition.

Eventually the true innovators in product and marketing leave, replaced by warm bodies who would push back on the efficiency seekers if only they could summon the courage. But everyone knows there’s no point. It is an unwinnable battle. Besides, retirement is only a few years away.

Enter Disruption

Fast forward some more and the company that was once seen as an untouchable monopoly is now being disrupted by a small, innovative, rapidly growing newcomer, eating its way up through the bottom end of the market in a way that nobody saw coming.

The threat is existential. Something must be done.

The shareholders scream to the board, “Innovate!” The board screams to the CEO, “Innovate!” The CEO echoes the screams to product and marketing, who in turn scream to their teams and outside agencies.

Everyone understands the existential requirement for innovation, but those in the trenches know—for it is now long-baked into the culture—that any innovation must be done efficiently, with as little waste as possible.

All of the departments whose mandate is efficiency-seeking don’t suddenly reverse course and say, “We’re okay with some waste now.” No, they play the game of pretending to innovate efficiently. A few know this is impossible, an oxymoron—they intuit the Innoficiency Principle—but there is no point in speaking up.

An efficiency-seeking department in an innovation-seeking company is optimized to the department’s goals and not the organization’s. The organization simply cannot fight the inexorable draw toward efficiency seeking, even when its very existence demands they fight it.

The Life Cycle of a Creative Firm

A successful creative firm follows a similar trajectory to its clients’ journey from innovation to efficiency. It too begins in a fireball of energy and disorder out of which magic is born.

Success eventually begets size which demands systems. The requisite efficiency seekers go from a pained minority to the governing class—they are the grown-ups without whom potential would never be turned into profit. The agency gets acquired by a holding company and the largest holdco-owned agencies serve the largest efficiency-seeking clients a high volume of low-margin and unspectacular work.

Both organizations are a sort of palliative care home for once-vibrant innovators, run by the efficiency seekers they tormented in their earlier years when chaos reigned, profit was elusive and magic was afoot.

Those with any innovative spirit have all left for new businesses and new agencies where they will seek each other out and try to make magic once again. The cycle repeats until the inevitable heat death of the universe, with entropy prevailing and all matter, energy and innovation dissipating into a homogenous sea of cold nothingness.

The Marketing Procurement Problem

So far we’ve been exploring the tension that resides within a company, but this tension exists between companies as well. Nowhere is this more obvious than when the client’s marketing procurement department—its most efficiency-seeking department—clashes with the innovation-seeking culture of an entrepreneur-led creative firm.

The marketing procurement problem is a version of the Innoficiency Problem. It is the mistaken idea that efficiencies can be brought to the procurement of creativity without negatively impacting that creativity.

Creativity, according to famed psychologist and author Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, is the ability to see—the skill of bringing a new perspective to a problem. Creativity is the idea that proceeds the innovation. It is the solution in theoretical form, that once it appears in the real world is what we call innovation.

A culture of creativity is a culture of innovation—of risk, of freedom to fail, of iteration, and, out of necessity, of waste.

The culture of a creative firm is messy and irrational; it is the home of the delinquent, the ADHD, the insufferable genius. It is a place where discussion of last night’s South Park episode, or of what’s trending on TikTok, is the job. To a procurement person, this mess is a problem to be solved, harnessed; to be reigned in and made more efficient.

There are many efficiencies to be gained in a large organization’s marketing budget, and procurement departments are right to pursue those efficiencies. But when the efficiency-seeking eye turns to the ideas themselves, the ideas are degraded.

Every agency that has ever dealt with procurement has had the frustrating experience of being told their thinking must be priced in units of doing—all so procurement can push for faster and cheaper thinking. This is the Innoficiency Problem again: the mistaken idea that waste can be eliminated from the creative process without impairing the output.

While possible in episodes, the aggregate effect is never anything but deleterious to that which is being procured.

“If You’re Efficient, You’re Doing it Wrong”

In 2017, Jerry Seinfeld, co-founder and co-writer of the most successful television show in history was interviewed by Harvard Business Review where he was asked about his creative process.

HBR: You and Larry David wrote Seinfeld together, without a traditional writers’ room, and burnout was one reason you stopped. Was there a more sustainable way to do it? Could McKinsey or someone have helped you find a better model?

JS: Who’s McKinsey?

HBR: It’s a consulting firm.

JS: Are they funny?

HBR: No.

JS: Then I don’t need them. If you’re efficient, you’re doing it the wrong way. The right way is the hard way. The show was successful because I micromanaged it—every word, every line, every take, every edit, every casting. That’s my way of life.

Action Required: Let’s Accept The Tradeoffs

My goal for this post is to bring to the business public’s consciousness the tradeoffs inherent in innovation and efficiency. To be ignorant of the Innoficiency Principle (that innovation and efficiency are opposable objectives) is to create the Innoficiency Problem and delude yourself and others in the organization into thinking you can increase one without decreasing the other, like driving a car in opposite directions at the same time.

Here are some questions for each of the relevant parties to consider.

To agency owners and leadership teams, I ask you to look at your own management and accounting systems and ask what the pursuit of billable efficiencies is doing to innovation and client value creation.

You started a business of ideas and advice and somehow ended up in a labor arbitrage business model. How did that happen? What price have you and your clients paid? Jay Chiat famously asked about his renowned ad agency Chiat/Day, “How big can we get before we get bad?” Is your noble pursuit of value creation and profit forcing unnecessary headcount growth instead?

To client-side procurement professionals, marketing is not a direct good and it is not a service in the same vein as janitorial or security. Make the distinction between the “logic” areas of marketing ripe for efficiency-seeking such as media buying and asset management, and the “magic” areas of creativity and innovation that are impaired by it. Redirect some savings from the former to the latter. You won’t get Jerry Seinfeld by the hour.

To client-side marketers, you have a constructive role to play in the negotiations between your agencies and your procurement department. The divide-and-conquer approach benefits no one.

Of the three parties in this relationship you have the most balanced point of view and you should be at the negotiating table to ensure that any savings being extracted from the agencies are not at the cost of your goals. You are the party placed to help procurement and the agency better understand each other. Accept the challenge.

To client-side CEOs and executive teams, innovation becomes harder with growth as the efficiency-seeking departments gain sway and move the culture away from innovation toward efficiency.

This movement is necessary but a keener eye needs to be trained on the tradeoffs being made. An efficiency- seeking culture pushes innovators out, so you want to create safe havens for innovators, free from efficiency constraints.

You want pockets of chaos and brilliance—special teams or business units—sheltered from those who would eliminate such “waste.” It’s on you to preserve the ability to innovate.

Let these special teams establish their own culture and don’t force assimilation. You don’t have to push against the greater innovation-seeking culture, you simply need to maintain the ability to innovate in pockets.

When it is time to unleash an innovation team, know that they won’t last a week without air cover from you. If the CEO does not understand the Innoficiency Principle and preserve pockets of innovation-seeking culture, the organization will eventually lose the ability to innovate altogether.

More to Come

This post was six years in the making—the most inefficient piece of writing I have ever undertaken—and I have left much unsaid. I will publish follow-ups in the future. Subscribe here to be notified.

Introducing 20%: The Marketing Procurement Podcast

Marketing procurement, and specifically “the marketing procurement problem” is the subject of my new podcast that I co-host with Leah Power from The Institute of Communication Agencies (ICA).

Leah and I have spent the last year interviewing marketing procurement professionals from some of the world’s largest companies, trying to get their answer to the question, “How do you procure creativity without killing it?” The podcast is called 20%: The Marketing Procurement Podcast and it’s available in all the usual places. New episodes drop every second Wednesday.